|

Anyone with long term pain will likely relate with this statement my sister recently made about her chronic back pain and exercise: "Yeah, the pain flare ups seem to be less frequent with exercise. But also feels hard to convince myself to exercise, because if I stretch too far it hurts real bad, too??" This situation is so common with people I see every day in the clinic. The pain has been there for a long time, but thinking on times that they've been most physically active, that tends to be the times that the pain has been its least intense, frequent and invasive. So if we know that staying active can change the intensity, frequency and overall impact pain has on our lives, why is it so hard to convince ourselves to do the exercises? Its an internal fight that a lot of people have with themselves. In practitioner language we call it Fear-Avoidance Behaviours, which basically means not doing the beneficial thing because of the fear of causing pain even if you know long term the beneficial thing reduces the pain intensity and/or frequency. It’s one of the biggest struggles for people with chronic pain.

I think a lot of the solution to it is finding a really enjoyable activity. In my sisters situation, she started taking MMA classes last year. A weird choice for someone who is already in pain, right? But even though shes learning some serious fighting moves and coming away with some proper bruises, her long term back pain has been more under control than it had been in ages. I explained it to her like this. "You’re not there to slug away at a pointless activity that you don’t enjoy. You have fun, you learn, it’s interactive, the people are nice and supportive, it’s social, it’s not 100% competitive, you get to do it as a family activity with Matt and the kids. So it’s probably so much more appealing than going for a run or going to lift weights at a gym by yourself for an hour a few days a week." And I think she got it! "Absolutely! Ohh that all makes so much sense... it's so true though. Going to the regular gym or even working out at home is like... ugh. No thanks. But going to MMA is so easy?! Because it's just fun... I mean, it's actually a really complicated work out, and some of it SUCKS... but is somehow so damn fun?!" While she's having all this fun kicking and punching, she'll definitely be using a lot of back muscles to coordinate and control the movements, and core muscles, hip stabilisers, all the areas that single exercise prescription focuses on. The difference is instead of doing separate specific exercises for each muscle group, it’s all just rolled into a sequence of movements and blows and dodges, mixed in with an instructor that makes her laugh and being able to spar with her partner. This is way more enjoyable for her than doing strict sets and reps of isolated exercises. Some people love doing the specific exercises, and guess what, thats awesome too because if you love it and enjoy it, you're more likely to do it! Lets talk neuroscience We already know that almost any kind of exercise produces endorphins, which are these wonderful little brain chemicals (neurotransmitters) that are natural pain and stress relievers. Endorphins act a little differently on the Peripheral Nervous System (all the nerves in your body that aren't part of your brain or spinal cord) and the Central Nervous System (the brain and spinal cord) They work by binding to opioid receptors in the Peripheral Nervous System. Its like your own personal stash of codeine, and your body makes it in response to exercise! They also work by reducing the amount of inflammatory chemicals that the nerve produces. In the Central Nervous System, endorphins also bind to the opioid receptors. Here their effect is to reduce another neurotransmitter called GABA. With GABA reduced, your brain is able to produce more dopamine - the pleasure neurotransmitter! Interestingly, these opioid receptors in the brain are most abundant in regions of the brain that control pain regulation. So how is it more helpful to have a fun active hobby? Researchers found that endorphin release varies depending on the intensity of the activity, suggesting that higher physical intensity leads to increased endorphins compared to more moderate activity. But is the endorphin rush better from a fun activity vs an activity that you find boring or tedious? I'm honestly not sure, but what I do believe with certainty is that most people are way more likely to actually DO the exercise if its something they find fun and enjoyable and actually have a desire to do it. Realistically, it probably doesn't matter WHAT you do, more that you just DO IT! Last week, I shared a bit about four interesting studies that look at pain. But I couldn’t stop at just four! So today, we’ll look at another four of the latest studies around how pain works, and what we can do about it. Mindful people experience less pain

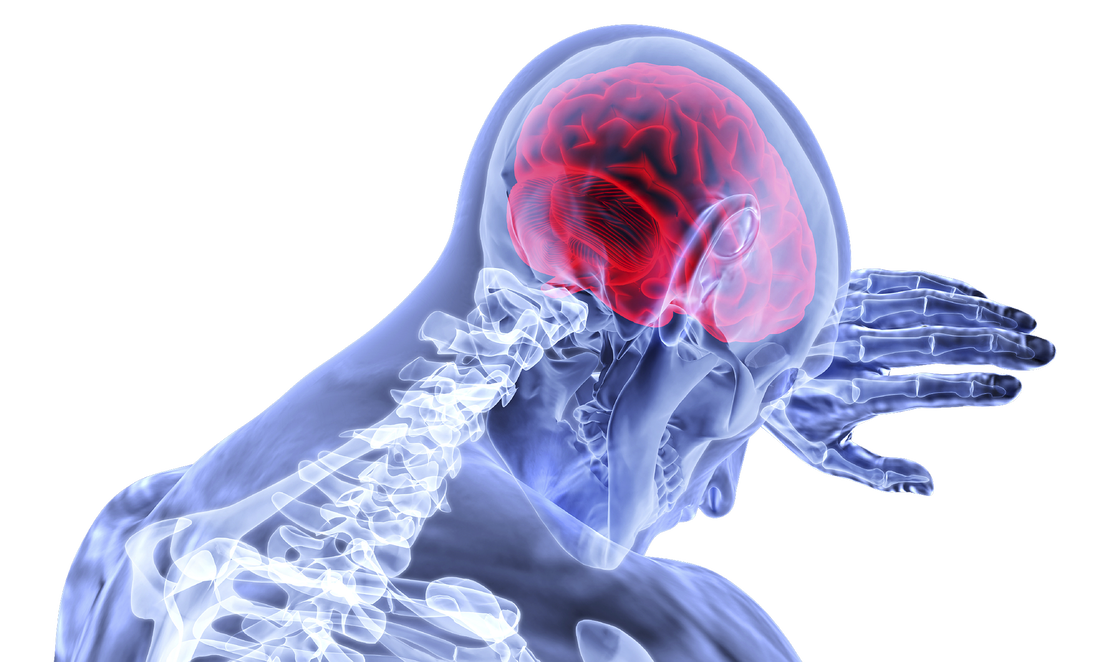

Some people just don’t seem to experience pain as much as others. One study has suggested that part of the reason why is mindfulness. What is mindfulness? It’s being in the present moment, rather than the past or future. When you are mindful, you are an observer of your experience rather than reacting with emotions and judgements. 76 volunteers with varying levels of innate mindfulness took part. Their brains were scanned as they were exposed to painful heat of around 49 degrees Celcius (aka a typical Aussie summer day, right?) The scans reveal that people who were more mindful did not activate an area of the brain called the posterior cingulate cortex as much as those who were less mindful. Those who reported high pain levels had a greater activation of the cortex. The researchers concluded that mindful people are less caught up in the experience of pain. You can’t change your in-born level of mindfulness, but there is other research that suggests that mindfulness practices can help with pain. This might explain why! Being hungry shuts off perception of pain Pain is a valuable experience for the human body. Without it, we would damage our bodies without realising the consequences! But chronic pain can lead to lethargy and exhaustion. So what if nature gave us a way to suppress chronic pain temporarily? Turns out, nature might have done just that. Researchers have pinpointed a group of 300 brain cells that prioritise hunger over chronic pain. They found that hungry mice would respond to acute pain, but were less fussed about longer-term inflammatory pain compared to well-fed mice. Further experiments revealed that the neurotransmitter NPY can block the inflammatory pain response when needed. This is a new area for more research, but it could reveal ways to inhibit chronic pain without shutting off acute pain. 'Tuning' the brain can alleviate pain Previous research has found that alpha waves are associated with relief of pain from a placebo effect, and can influence how different parts of the brain process pain. So researchers looked into whether ‘tuning’ the brain to alpha waves can reduce pain. The experiment involved flashing light or playing noise that were in the alpha range. Both of these interventions significantly reduced intensity of pain. The researchers are now looking into how effective these are for different pain conditions. It’s early days. But soon, you could be watching YouTube videos or listening to meditations in the alpha range that are able to reduce your pain! Does an exploding brain network cause chronic pain? Hyperactive brain networks could be why people with fibromyalgia experience hypersensitivity. Their brain networks are primed to react with rapid and system-wide responses to minor in response to minor changes. This is known as explosive synchronisation. The researchers looked at the electrical activity of women with fibromyalgia. There was a strong correlation between the hypersensitivity of the brain and the intensity of pain reported by the women. This suggests that a chronic pain brain is electrically unstable and sensitive. So the next time someone asks you about your fibromyalgia, tell them it’s your exploding brain network! In case you haven’t figured out, supporting people with chronic pain is my passion. If you’re looking to work with a health professional who will work with you on your journey to recovery, book a myotherapy appointment today. It’s no secret that I’m a bit of a research geek. Scientists everywhere are exploring the experience of pain and how we can alleviate it. So I thought I’d share some of the most recent findings about pain. Some of these you might be able to apply in your daily life. Some you might like to share with your healthcare providers. And some are just interesting to know! Men and women remember pain differently

Scientists have theorised for years that chronic pain is related to memories of earlier pain. One team has found that men remembered a previous painful experience quite clearly. This made them hypersensitive when they were returned to the location of that experience. On the other hand, women were less stressed about their experience. The same researchers did the same experiment on mice, and ‘blocked’ the memories of male mice. When they ran the experiment with the blocked mice, they did not show signs of being stressed by the previous pain. The brain cells that make pain unpleasant If you step on a sharp object, your nerve cells in the brain tell you two things – there’s a piercing sensation in your foot, and that it’s not a nice feeling. But a team of scientists have discovered the brain cells that tell you all about that not-so-nice feeling – these brain cells are responsible for the negative emotions of pain. In an experiment with mice, they were able to identify a group of neurons in the basolateral area of the amygdala (often called the fear centre of the brain). When the mice experienced pain, these neurons would fire. But when this bundle of neurons was turned off, the mice didn’t experience the discomfort of pain. They were still able to feel and respond to sensations, but pain was no longer unpleasant for them. Pain as a self-fulfilling prophecy Have you ever flinched at something that you expect to hurt? The latest research suggests that you probably will feel pain, even if it doesn’t cause pain. Say what? If you expect pain, your brain will respond to that pain. Researchers scanned the brain of people who were exposed to low heat and high, painful heat. The participants were shown cues to suggest whether the heat was going to be low or high. When the heat was applied, they rated their pain. But what they didn’t realise was that the cues didn’t always correlate to the heat they received. When they expected high heat, brain regions around threat and fear were activated while they waited. When the heat was applied, there was more activity in the pain regions of the brain – even if it was a low heat. This may be part of why chronic pain lasts long after the damage to tissue has healed. Genes associated with chronic back pain discovered Chronic back pain is actually the number one cause of years lived with disability world-wide. So scientists are looking at all of the factors that might contribute to it. Recently, researchers have uncovered three gene variations that are associated with chronic back pain. The study looked at the genes of 158,000 people, including 29,000 that had chronic back pain. Then they looked for the genes that popped up for those with chronic back pain. One gene variant, SOX5, is involved with development of the body in the womb. If it’s turned off, it causes defects in cartilage and bone formation. A second gene that was already associated with disc herniation was linked to chronic back pain. The third was a gene that plays a role in the development of the spinal cord. This might not cure your chronic back pain, but it does help researchers to pinpoint the structures and processes involved. In the meantime, make sure you get yourself booked for a myotherapy session! There were so many interesting research papers that I have pt 2 coming up next week! If you don’t want to miss out, make sure you’re following my Facebook page. There, I share tips, info and insights into chronic pain management and myotherapy. Everyone has experienced pain at one time or another. But pain is personal – each of us experiences pain differently. Some of us feel it very intensely, and others not so much. This is because pain depends not only on what happens to your body, but also how your brain responds to it. This is what is known as the Pain Matrix. What is the Pain Matrix?

This matrix processes information from the nerves that tell us when we’re in danger or injured. It responds by increasing or decreasing our sensitivity to these messages. These changes – known as top-down regulation – control how intensely we feel pain. The Pain Matrix involves different areas of the brain that control emotions, behaviour, movement, perception and thoughts. So it’s no surprise that when you’re in pain, all of these different factors can change. How does the Pain Matrix work? There are two main changes that the Pain Matrix can induce. Anti-nociception is a reduction in sensitivity to pain, whereas pro-nociception is an increase. Anti-nociception uses the body’s natural painkillers – endorphins – to block the danger signal and decrease the pain response. Ever seen someone injure themselves in a dangerous situation, like in a car accident, but they can still move to safety without feeling pain? This is because a rush of endorphins temporarily blocks out the message of danger so they can get to safety. On the other hand, pro-nociception is usually due to swelling and chemical changes in the nerve endings around an injury. Have you ever had a bad paper-cut? Your sensitivity is much higher around the cut, even if you’re not touching the injured part. Sometimes, even moving the other fingers can hurt. Changes in the brain = changes in the pain Despite what we used to believe, the brain can continually change its form and function as a form of adaptation. These changes are known as Neuroplasticity. Nerve pathways can physical alter by increasing or reducing the number of connections. Or they can alter the release of neurotransmitters – more stimulating neurotransmitters means more nerve activity, which can increase the sensitivity of the system. When it comes to chronic pain conditions, the central nervous system is reorganised. This can include damage to nerves, leading to abnormal connections between them. Pain is more likely to occur than not, as pro-nociception increases and anti-nociception is impaired. This can lead to exaggerated responses to pain including pain caused by non-painful experiences - this is known as allodynia, and can be a common symptom in conditions like Fibromyalgia. Long term inflammation can lead to a heightened sensitivity of the nervous system. In the presence of inflammation the amount of nerve stimulation needed to send the signal decreases and the nerve firing rate increases. With so many danger messages coming in when there is inflammation present, the nervous system starts to respond on high alert by using its protective mechanism - pain! Controlling the pain There is no one size fits all approach to controlling pain, but theres increasing evidence that changes to pain intensity can be influenced by more than just the incoming messages from our tissue - it can also be influenced by our perceptions of danger and safety. This is likely due to the pain matrixes involvement in areas of the brain that deal with emotions, behaviours and thoughts. Pain experts Dr Lorimer Moseley and Dr David Butler of the NOI Group have published a fantastic book called Explain Pain that describes DIMs and SIMs - that is, Danger In Me (DIMs) and Safety In Me (SIMs). They say that any credible indication of danger can increase your perception of pain, and likewise a credible indication of safety can decrease the pain. We'll dive deeper into this research in future blogs. The Gate Control Theory involves a more physical approach to pain control. Have you ever bumped into something, then rubbed the area to make it hurt less? The Gate Control Theory is that non-painful sensations such as pressure can block or override the danger messages and reduce pain. The nerves that tell us about pressure are faster and more effective than those that tell us about danger. This might be part of why something like a good massage session helps with pain. Massage is also a great way to stimulate some feel-good endorphins, which promotes anti-nociception to reduce painful sensations! If you’re looking to minimise your pain, a combination of massage, exercise therapy and other myotherapy treatments can help. Have a look at my online booking calendar to book in for an appointment. Everyone knows someone who is a bit of a klutz. But often, there is a reason behind someone being naturally clumsy. It all comes down to what we call proprioception. What is proprioception?

To put it simply, proprioception is a fancy way of describing where your brain perceives your body to be in space. If you have good proprioception, your brain knows that your arms and legs are where they are. But if you have issues with proprioception, your brain might think that you’re a little more to the left or right of where you actually are. This is where it’s common for people to do things like walk into doorframes, stub their toe or miss a step. Some people can be born with a reduced sense of proprioception, particularly if they have neurological conditions such as autism. Others may have proprioceptive issues because of hypermobile joints. Sometimes, proprioception of a particular body part can be reduced through injury, such as a dislocation. What are signs of proprioception issues? There are some common signs of proprioception issues, including:

It can also come with other signs, depending on the cause. Proprioceptive issues will come with sensory signs in people with autism. Hypermobile people will often experience more injuries such as rolled ankles because they have more flexible joints than most people. Have you ever noticed that if you have an injury, you will be more likely to bump that injured limb or area? Thats because that area is where the misinformation is coming from - for example, I cut my finger a few weeks back, and managed to bump it on something on at least 3 different occasions that day! My general awareness of that finger was raised, but my ability to hone in on the location-specific proprioception was decreased due to injury. How can I fix my proprioception? The good news is, you can work on your proprioception and reduce the clumsiness. Proprioception is influenced by information from your nervous system and your balance. Here are some ways to retrain your brain and increase body awareness. Move your body A lot of people will avoid exercise because they think they are clumsy. But the more that you move your body, the more chances your brain gets to correct itself. So don’t avoid exercise – just stick to gentler options while you retrain your brain. Retrain your balance There are specific exercises that can challenge proprioception and retrain the brain. Stability and balance exercises are the most effective. These start with very simple and supported movements, then increase in difficulty as your proprioception adapts. For example, you might stand on one leg with your eyes open. Once you can do that easily, movements of your raised leg can be included which will challenge your balance. If that becomes easy, you can try it with your eyes closed, or add a wobble cushion or balance board. Exercises will need to be tailored to your specific proprioceptive needs. As you can see from the example above, there are many stages of these exercises that progress to harder and more challenging movements as your proprioception enhances. Neurons that Fire Together, Wire Together Have you heard this phrase before? The brain loves short cuts, so movements, actions, thoughts and sensations that are often felt together can become neurally linked. We can use this to our advantage by using exercises and movements in a way that can "rewire" the proprioception of a joint so it relearns its movement or activation patterns. Taping Using tape can help to retrain your proprioception in conjunction with stability exercises. It helps to indicate where the body part is because the tape is slightly stretched on your skin for a number of days - your brain gets a consistent signal from the sensation receptors on the skin saying "Hey! Here I am!". Taping can also help with holding the joint or body part where it should be, preventing issues such as hunching or rolling of the shoulders. It’s best to get taping done by a qualified practitioner who can tape you correctly. This is why I offer taping sessions for my clients who need re-taping between appointments. Do you want to work on retraining your brain and increasing your proprioception? We can put together a personalised management plan to help. Try your first treatment for $97 (normally $115!) Book in an appointment today to get started. |

Meet Our Team

We have a team of great practitioners available 7 days a week at our Rowville clinic. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

Got a question about Myotherapy?

Contact Mel by phone, email or Facebook

|

Simple Wellness Myotherapy & Remedial Massage Clinic

Shop 12B 150 Kelletts Rd Rowville VIC 3178 |

Phone us on

03 8204 0970 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed